Eli Heuer 2022, image license: CC0 “No Rights Reserved”

I have been experimenting with new business models for independent libre (open source) font development recently. I had my first hint that these models might work when my project GTL Type Label minted all 100 editions of its first font NFT. Enough people have been curious about what I am doing since then that it seems like the right time to put some of my thinking around libre type and NFTs into an essay.

GTL001 Alpha NFT floor price viewed from Rainbow App, image license: CC0 “No Rights Reserved”

I am not going into much detail here about the philosophy behind libre type and why I sometimes use the word “libre” instead of “open source.” Basically, I think that the cultural nature of typefaces, and the way they lend themselves to being forked to create new typefaces, makes fonts uniquely well suited to be licensed under a copyleft license like the OFL. Two documents are foundational to my thinking about licensing for font software and are recommended reading for anyone who wants to better understand my perspective:

1: Dave Crossland’s 2008 University of Reading MATD Dissertation

2: Richard Stallman’s 1985 GNU Manifesto.

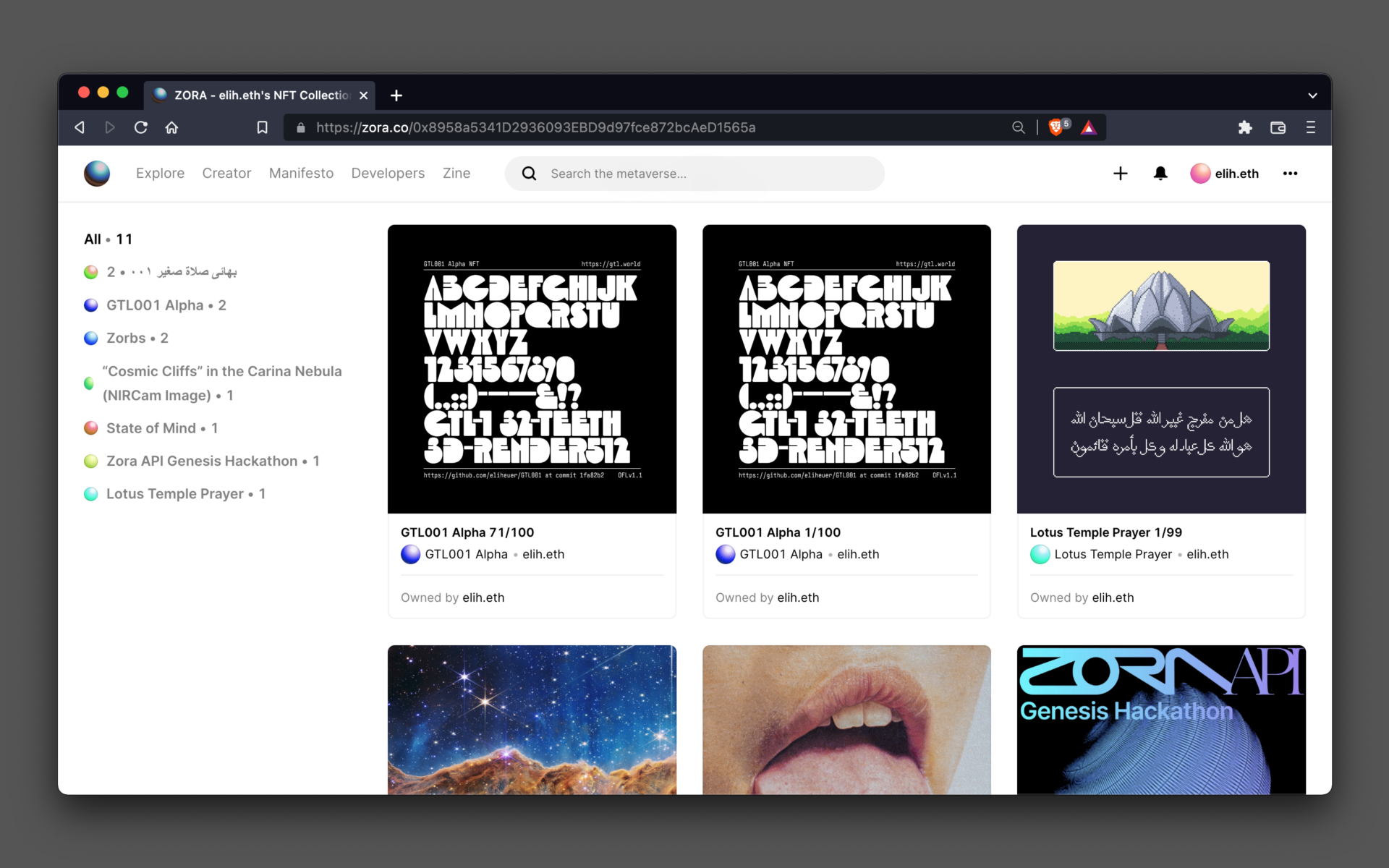

I am not a free software maximalist, and I am well aware of the shortcomings of the ideas from the above documents in practice, as well as the problems with permissively licensed open source software around value capture for developers and software freedom for users. Without my experiences with the reality of open source software development, I am not sure if I ever would have become interested in Ethereum. What attracted me to this space was a culture of trying to fix many of the misaligned incentives in Web2. Specifically, projects like GitCoin, and concepts like Hyperstructures, NFTs, DAOs, quadratic funding, and retroactive public goods funding were all very interesting to me as I fell down the crypto rabbit hole.

Image source: Kevin Owocki on Twitter. Listen to the printer story here.

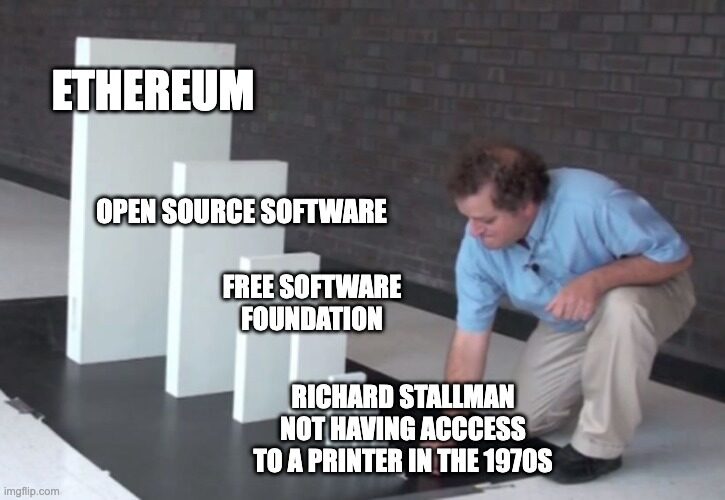

Below is the tweet announcing the first font NFT from GTL. The image associated with the NFT is a specimen showing the typeface GTL001 at its alpha release. The image was created with a Python script using DrawBot-Skia, a version of DrawBot that works on Linux. The script is included in the GTL001 Git repository if you want to use it or just take a look at how the image was made. The auxiliary monospace text is set in Hasubi Mono, an Arabic/Latin monospace typeface I designed, which I am currently preparing for a release on Google Fonts.

✨My first font NFT is now minting on Zora!

— elih.eth (@eliheuer) July 30, 2022

It is a specimen of the alpha release, so think of it like a rookie card for a typeface.

The font is open source and licensed under the SIL Open Font License, Version 1.1.

Mint link: https://t.co/gRImiAn73r pic.twitter.com/Ihy8QsjPpd

What I am trying to do with this approach is to create two separate but linked goods with different economic properties, a public good, and a veblen good. Libre fonts are best understood in economic terms as public goods. Here is the definition of public goods from Wikipedia (also a public good):

“In economics, a public good (also referred to as a social good or collective good) is a good that is both non-excludable and non-rivalrous. For such goods, users cannot be barred from accessing or using them for failing to pay for them. Also, use by one person neither prevents access of other people nor does it reduce availability to others. Therefore, the good can be used simultaneously by more than one person. This is in contrast to a common good, such as wild fish stocks in the ocean, which is non-excludable but rivalrous to a certain degree.”

Image source: Twitter

And the definition of a veblen good, also from Wikipedia:

“A Veblen good is a type of luxury good for which the demand increases as the price increases, in apparent (but not actual) contradiction of the law of demand, resulting in an upward-sloping demand curve. The higher prices of Veblen goods may make them desirable as a status symbol in the practices of conspicuous consumption and conspicuous leisure. A product may be a Veblen good because it is a positional good, something few others can own.”

Ether (ETH), the native token used by the Ethereum blockchain, is itself sometimes considered a veblen good. As I am writing this, the Ethereum mainnet merge, which will reduce Ethereum’s energy consumption by 99.95%, has been tentatively scheduled for around September 15th/16th 2022. The price of ETH earlier this year was around $1000 briefly, but with the merge date confirmed and the final testnet merge completed, the price has grown to around $2000. I bought some ETH at $1000 (not nearly enough I now realize) but now at $2000, my desire to buy ETH is much greater. There is a fear of missing out as the price rises that does not exist right after a crash in the price, the same dynamic plays out with NFT floor prices.

On the other hand, the software that runs Ethereum is a public good. This is the origin of the public/veblen good concept for me. The Ethereum ecosystem even uses a lot of copyleft licenses instead of permissive licenses. Notably Go Ethereum AKA “geth”, Solidity (the smart contract programming language), and the Uniswap interface are licensed under copyleft GPL-3.0 licenses.

When you use and benefit from crypto, you tend to adopt crypto values. So free and open source programmable money and the opportunities it provides might be a good way to get more people to care about copyleft values, as opposed to berating anyone who says Linux instead of GNU/Linux, which does not seem to be working out well as a tactic.

The Monotype Helvetica NFTs feel a bit awkward to me because Monotype’s practice of tightly controlling and locking down intellectual property does not align well with the open, collaborative, and meme-driven culture of crypto I enjoy. If there ever was a typeface that wanted to be licensed under the OFL, it is Helvetica. NFT projects like Nouns use a CC0 “No Rights Reserved” license to help their images become memes and create a community that participates in building the brand. Some NFT projects even use the copyleft Viral Public License. Free culture has a home-field advantage with crypto that it does not have with traditional finance.

If a font released under the public/veblen good model becomes a meme or gets a lot of use, the alpha release specimen might be worth something as a collectible. This would reward people who originally minted the NFT and give them a stake in seeing the typeface become widely used and well known. The fact that font files can be copied easily becomes an advantage in this model. The more people that have the font files, the better. A designer might have a portfolio of OFL font NFTs and would be financially motivated to use those fonts well and help them become popular or infamous. The goal is to create a positive-sum game between type designers and users. If the font does not go anywhere after the alpha release mint, it is a relatively inexpensive NFT (GTL001 was 0.009ETH) that is a public receipt (viewable from Web3 apps like Rainbow or Zora) for funding independent open source software development. Besides just a floor price, a sign-in-with-Ethereum button on a website allows for many different business models built around token-gating.

GTL001 NFTs, viewed from Zora

Ideally, font NFTs could create better incentives for contributing to libre font projects and encourage collaboration. An NFT holder might make issues on the Git repository for a font project hoping the floor price will go up, or even make pull requests improving the source files and other parts of the project. Or a group of people wanting to make new fonts for a script not well served by the traditional font industry could form a DAO funded by NFT sales.

The final paragraph of Dave Crossland’s thesis almost seems to predict a positive-sum business model like this emerging:

“While today’s professionals use proprietary business models, the biggest problem facing new type designers is obscurity. Treating customers as friends rather than thieves and type design as a service instead of a product may prove an effective way for newcomers to enter the market while reinforcing a free society in the age of computer networks.”

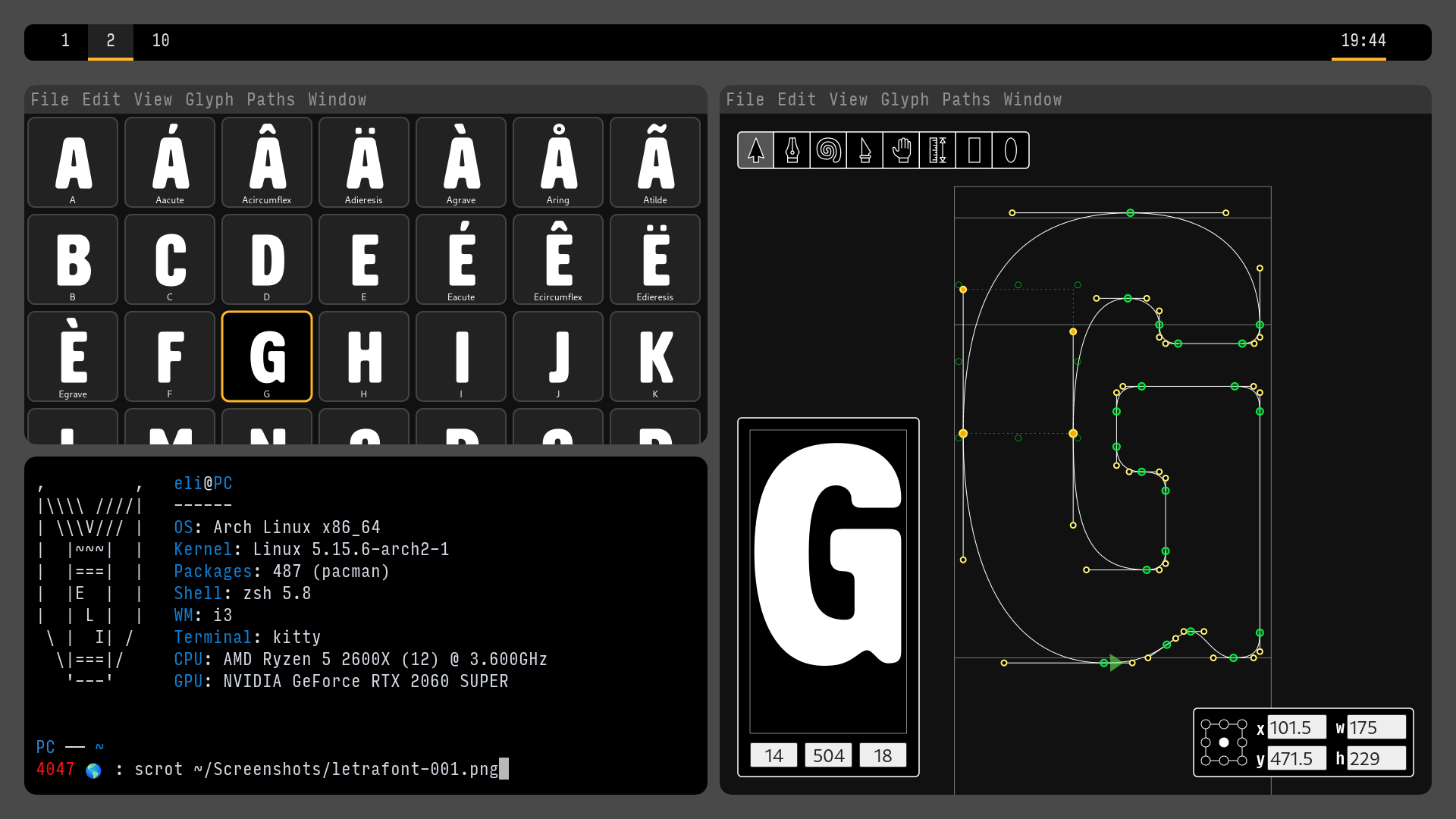

GTL002 in development using LetraFont(a fork of Runebender) on Arch Linux

I realize buying an NFT for a font that can be downloaded for free from a Git host might still seem insane to some people. Especially people looking at Web3 from the outside, but imagine if no one had thought of proprietary font licensing as we know it today and tried to introduce it in 2022. It might seem strange to pay for an infinitely copyable font file, and then not have the ability to resell the license on a secondary market or make changes to the font to suit your own needs. Maybe font NFTs and proprietary font licenses are equally absurd ideas, one just seems normal because it is familiar and established.

About Eli Heuer

Eli Heuer is a software developer, type designer, and the founder of GTL Type Label. Eli started designing fonts while working in the game industry as a UI designer who needed to edit pixel fonts to expand language support. He has contributed to many attempts at creating free and open source font editors, such as TruFont, Runebender, LetraFont, and (minimally, hopefully, more in the future) MFEK. He has done font engineering work for many fonts in the Google Fonts collection and has contributed to Google Fonts related software projects like gftools and googlefonts-project-template. His Arabic and Latin monospace typeface Hasubi Mono is coming soon to Google Fonts and he is in the process of starting a Baháʼí/Islamic Studies book publishing project with a self-imposed design constraint to use only OFL licensed fonts.